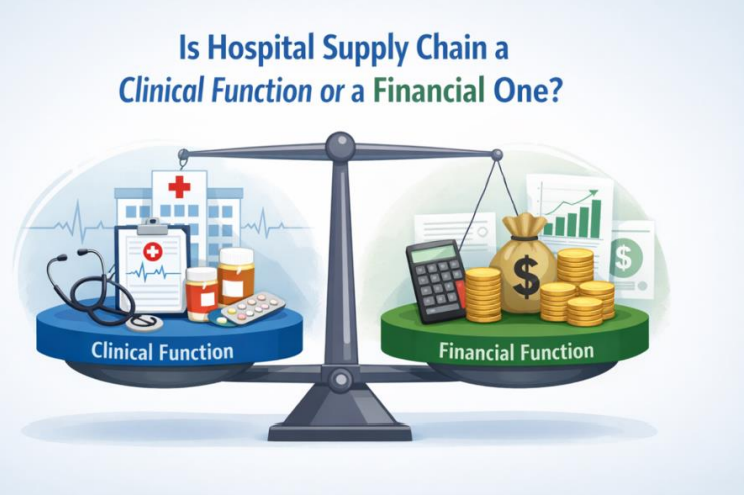

Is Hospital Supply Chain a Clinical Function or a Financial One?

By Sotiris Tsiafos – Tsiaras, Pharmacist and Hospital Supply Chain Leader, published on LinkedIn on the 16 February 26.

Every Hospital eventually finds itself trapped between two realities that seem to contradict each other:

On one side, there is the clinical expectation that medicines, consumables, and critical devices must always be available, because healthcare is not an industry where delays can be tolerated. On the other side, there is the financial reality that every product sitting on a shelf represents capital that has already been spent, and that expired stock is not merely an operational inconvenience but a direct and measurable loss.

Is hospital supply chain primarily a clinical function, whose purpose is to protect patient care regardless of cost? Or is it fundamentally a financial function whose purpose is to protect budgets, enforce spending discipline, and ensure that resources are not wasted? Most hospital leaders recognize both problems, but very few stop to ask the deeper question that sits underneath them: who truly owns inventory decision inside a hospital?

Two Rational Logics That Rarely Meet

The clinical logic is straightforward and deeply rooted in the mission of healthcare itself. If a medicine is prescribed, it must be available. Stockouts are not minor disruptions; they can become patient safety events because in a hospital environment the consequences of unavailability can escalate quickly. From this perspective, holding extra stock feels responsible, even necessary.

The financial logic is equally valid. Inventory is cash converted into product.

Overstocking reduces liquidity, distorts budgets, and creates expiry risk. From this perspective, excess stock is not “safety,” it is inefficiency hidden on a shelf. From this perspective, inventory is a financial asset that must be tightly controlled, not a clinical comfort blanket.

The challenge is not that one logic is correct and the other is misguided. The challenge is that both are valid, but they are rarely integrated into a single decision-making framework.

Where the Conflict Becomes Operational

This tension shows up every day: Pharmacy increases safety stock after supplier delays, trying to protect treatment continuity. Finance later sees rising inventory value and questions spending discipline. Procurement hesitates to approve orders because budgets are tight. Emergency orders follow, often at premium prices, reinforcing the perception that the system is uncontrolled.

Technology, ironically, often reinforces the problem rather than solving it. ERP systems are typically built with a financial lens. They do not naturally account for the reality that in healthcare, not all shortages carry the same consequences. The result is predictable: clinical teams work around the system to protect care, real consumption happens outside the visibility of the system, and workarounds quietly become normal practice.

This is why so many hospital leaders misdiagnose the problem. They assume it is a process issue, or a discipline issue, or a procurement issue. In reality, it is a governance issue disguised as a logistics problem. What looks like inefficiency is often something else: a governance gap.

A Governance Problem Disguised as a Supply Chain Problem

In many hospitals, responsibilities are fragmented: Pharmacy holds stock, Procurement manages suppliers, Finance controls budgets and IT owns the system. Everyone owns a piece of the puzzle, but no one owns the underlying decision logic that defines how patient risk should be balanced against financial risk. As a result, inventory policy becomes informal, decisions are made under pressure, and accountability becomes blurred. When things go wrong, the conversation turns predictable: pharmacy over-ordered, procurement delayed, finance blocked the PO, the system didn’t work. In reality, the hospital never defined what “acceptable risk” looks like, nor who has the authority to decide it.

Clinically Led, Financially Governed

Hospitals do not need to choose between clinical ownership and financial ownership. They need a model that is clinically led and financially governed.

That starts with recognizing that not all stock deserves the same strategy. A life-saving medicine with no substitute should not be managed with the same logic as a routine consumable. Inventory must be stratified by clinical criticality, not only by cost or historical consumption. It also requires service levels to be explicit. Instead of arguing about “how much stock to hold,” hospitals should define what probability of stockout is acceptable for each category. That reframes inventory management into what it truly is: risk management.

Finally, decisions must be governed jointly. Pharmacy cannot carry this alone, and finance cannot define availability targets alone. A small cross-functional authority (pharmacy, procurement, finance, and clinical representation for high-risk categories) can formalize trade-offs before crises force reactive decisions. ERP systems remain essential, but they are not sufficient. They are financial engines, not clinical risk engines. Without decision-support layers that account for criticality, lead time volatility, and supplier reliability, “optimisation” becomes little more than accounting.

The Real Cost of Getting It Wrong

When hospitals fail to resolve this question, the cost accumulates quietly: unnecessary overstocking, recurring emergency orders, expiry write-offs, constant firefighting, and eventually staff fatigue and interdepartmental mistrust. A hospital with full shelves can still be fragile because its stock may be poorly distributed, poorly governed, or full of products that do not match actual clinical demand. Perhaps most dangerously, risk becomes invisible. A hospital with lean inventory can still be unsafe because the savings may have been achieved by stripping away resilience. Without a shared decision framework, leadership cannot confidently say which one they are.

So, What Is Hospital Supply Chain?

Hospital supply chain is not purely clinical, and it is not purely financial. It is neither, at least not in isolation. It is best understood as a clinical risk management function operating under financial governance. Until hospitals treat it that way, they will continue to swing between two expensive extremes: stockouts and waste -and call both “unavoidable,” when in reality they are often the predictable outcome of unclear ownership.

The question is not whether clinical or financial logic should dominate. The real question is whether the organization is mature enough to formally integrate both into one coherent governance model.